Valuation, liquidity preferences, and anti-dilution provisions are three key terms in a startup term sheet that can have small nuances that lead to outsized economic impacts.

Securing your first venture capital investment to fuel your startup’s growth is a major milestone that often opens the door to additional funding opportunities as your business scales. The term sheet is an essential part of finalizing the deal that outlines the overall key terms and requests of the investor. Although not legally binding, once signed, it acts as a blueprint for the formal legal documentation and due diligence that will follow, making it critical for founders to understand. The right investor can be instrumental to a company’s success, so establishing a mutually beneficial partnership from the outset is key.

There are numerous terms in the term sheet regarding economics, however this article will focus on valuation, liquidity preferences, and anti-dilution provisions—all of which can have small nuances that can have outsized impacts on your startup.

Valuation

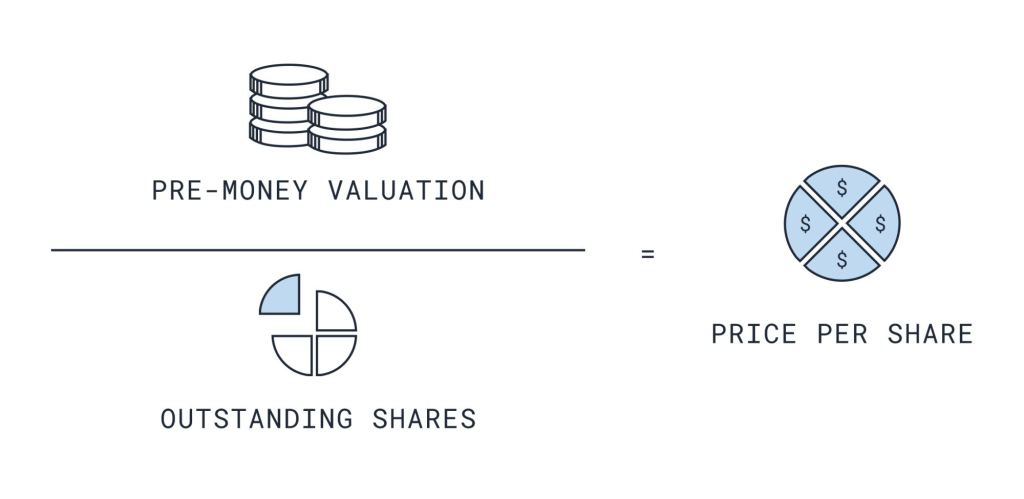

Easily the most contested and negotiated part of the term sheet, the valuation is a single number quantifying how much the company is worth. The pre-money valuation is the amount investors are willing to pay for shares of the business before the investment. The company’s price per share is calculated by dividing the pre-money valuation by the outstanding shares prior to the round.

The post-money valuation is what the company is worth after the round and is equal to the pre-money valuation plus the investment.

Valuation is indeed an important factor, and often collapses deals given its visceral connection to founders who’ve put their blood, sweat, and tears into the business. But this doesn’t need to be the case. Although a lower valuation will provide the investor more equity in the business, the actual change in ownership is often incremental in comparison to the change in valuation. A (reasonable) range of valuation may only result in incremental changes on the cap table.

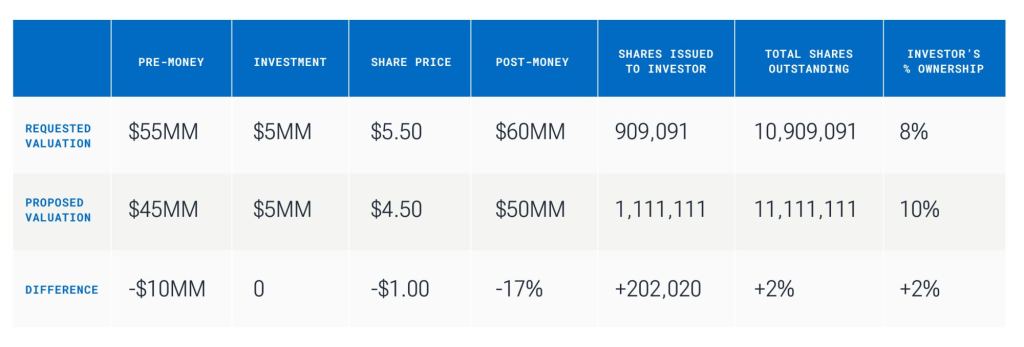

Example of the impact of a lower valuation

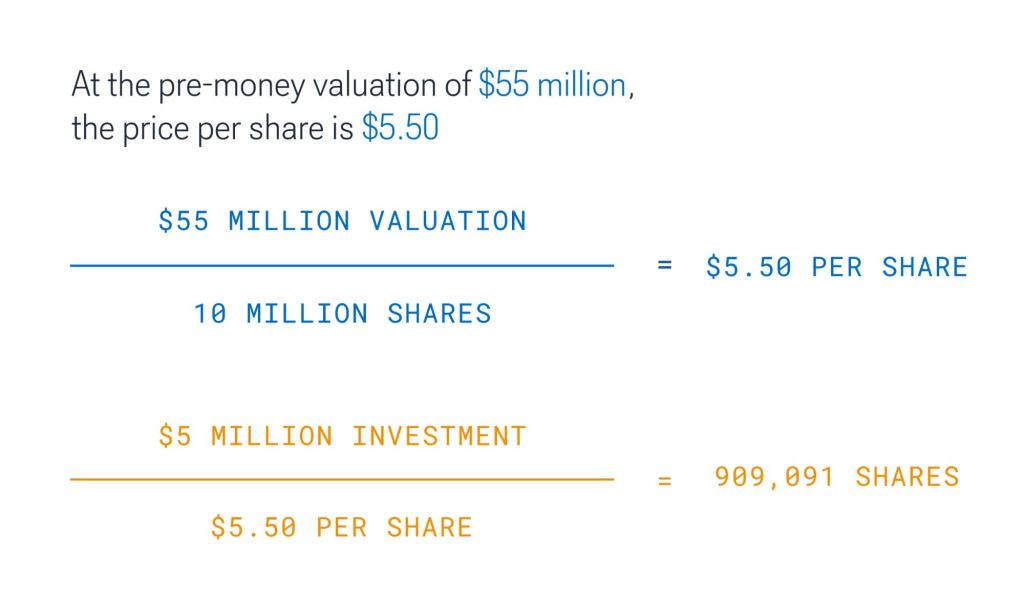

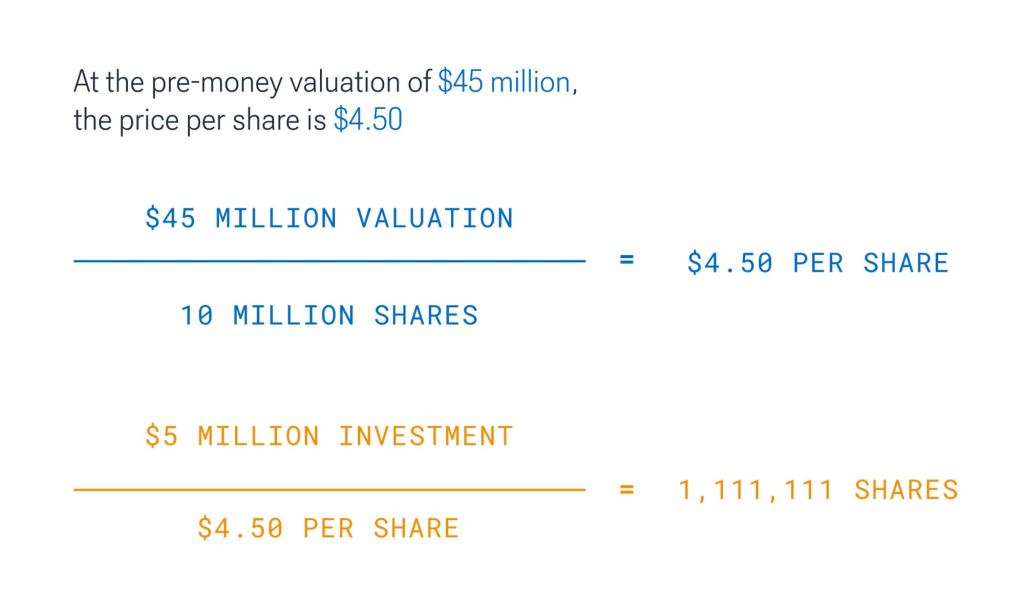

An investor is looking to invest $5 million in a startup. The startup’s two co-founders have 100 per cent ownership of the company and 10 million shares outstanding. They have requested a pre-money valuation of $55 million ($60 million post-money). The investor proposes a lower pre-money valuation of $45 million ($50 million post-money).

The investor will receive 909,091 shares, or 8 per cent of the 10.9 million fully diluted shares (10 million shares + 909K shares issued).

The investor will receive 1.1 million shares, or 10 per cent of 11.1 million fully diluted shares (10 million shares + 1.1 million shares issued).

*Figures are approximate.

At the lower pre-money valuation, the investor is issued more shares. As a result, the investor’s fully diluted ownership (FDO) increases from roughly 8 to 10 per cent, and each co-founder’s ownership decreases by 1 per cent.

As the example indicates, changes in valuation are not directly proportional to changes in ownership. A post-money valuation decrease of 17 per cent results in the co-founders losing only 2 per cent FDO (1 per cent each).

Another way to think about it is in terms of shares. At the lower valuation, the total shares outstanding after the round only increases by 2 per cent which is the investor’s additional ownership. This marginal growth in dilution is shared by each co-founder (at 1 per cent each).

What to consider when negotiating valuations in a term sheet

The term sheet has several financial levers and valuation is just one of them. If you’ve received a term sheet with a valuation that is lower than you expected, consider the difference from a dilution sensitivity perspective and even model it yourself. Yes, a lower valuation technically means more dilution of ownership, but angel and VC investors add substantial value in terms of capital, network, and support.

More often than not, it’s worth taking marginally more dilution from the right investment partners as they will accelerate the company’s growth. For the time being it’ll mean a founder holds a somewhat smaller slice, but the investor is focused on growing the whole pie.

As the example above indicates, because the two co-founders own 100 per cent of the company, they have borne all the dilution from the investor. But as the cap table grows to include more shareholders, the dilution from additional equity capital will be more broadly distributed. This is because the cap table is a zero-sum game: any increase in one shareholder’s fully diluted ownership is borne by the rest. In other words, one shareholder’s increase decreases the ownership of every other shareholder.

Liquidation preferences

Next to valuation, liquidation preferences is the most financially impactful term in the term sheet. Essentially, a liquidation preference provides the investor who has preferred shares with an additional return on top of their investment when the company exits (such as an IPO, sale, or liquidation). This term can significantly affect the founder’s return since preferences are paid out before the common shareholders receive anything. There are three degrees of liquidation preferences:

- Non-participating

- Capped participating

- Fully participating

Non-participating preferences

Non-participating means that in a liquidation event, the investor receives the greater of: their preferred share value if they were to convert their shares to common shares, or a multiple of their investment (usually 1X the investment amount).

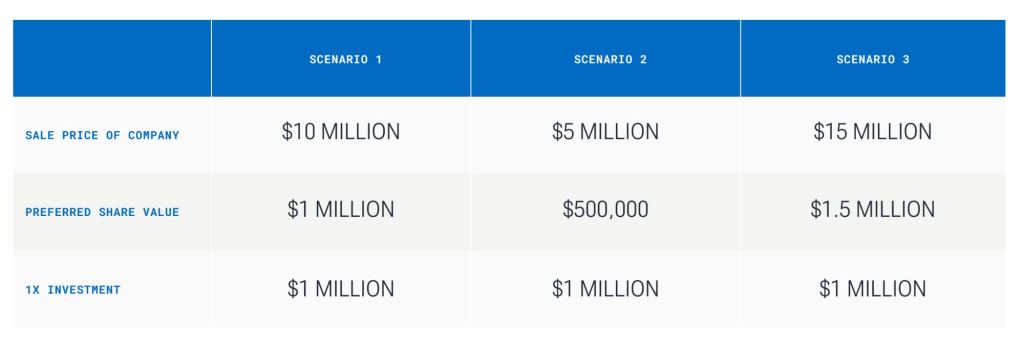

Example of a non-participating preference

An investor owns 10 per cent of a company, originally investing $1 million with a 1X non-participating preference.

- If the company sells for $10 million, both preference options yield the same value and the investor receives $1 million.

- If the company sells for $5 million, the investor will trigger their preference and receive $1 million at 1X their investment, rather than convert their shares to receive $500,000.

- If the company sells for $15 million, the investor will convert their preferred shares to common and receive $1.5 million ($15MM x 10%), rather than receive 1X their initial investment.

Participating preferences

Participating preferences allow the investor to receive both a return based on their percentage of ownership and the multiple set in the preference. There are two types: capped participating preferences and fully participating preferences.

A capped preference means the investor will receive their investment multiple (usually 1X) plus they get to convert into common shares and participate on a pro-rata basis in the remaining proceeds. For example, if the investor owns 10 per cent of the company, they receive 10 per cent of the remaining proceeds (after receiving their 1X investment multiple). This is capped once they reach a target aggregate amount of capital returned (i.e. 3X their investment).

Fully participating preferences have the most significant impact on the founder’s return. They provide the investor with both a multiple of their investment amount (usually 1X) plus the right to convert to common shares to receive their ownership’s slice of the remaining proceeds, without any cap.

Example of participating preferences

A company raises $50 million from investors that have a 1X liquidation preference.

If the company is sold for $50 million or less – all the proceeds will go to the investors (if they were the only financial partners).

If the company is sold for $51 million – only $1 million is available for common equity participation—which also includes the investors if they have a participation mechanism.

What to consider when negotiating liquidation preferences

When negotiating this section of the term sheet, founders should keep in mind that preferences are paid out before the common shareholders get anything, and only participate in the incremental amount above the liquidation preference. In fact, depending on the value at liquidation, founders may be left with nothing.

Although founders may have little appetite for liquidation preferences in the term sheet, there is rationale behind the mechanics. Investors are committing to illiquidity for up to a decade when they invest in a startup, and the liquidation preferences are considered a premium for having their capital locked up. Consider the effects of the same amount that’s allocated to a public market equivalent with 10 years to appreciate. Some may argue that the investors, having invested at such a low valuation, can expect outsized returns. However, investors believe the risk profile of startups warrants greater capital protection—and, VCs have investors to answer to as well.

That said, non-participating preferences are the most commonly used in term sheets, and those that require more than 1X may warrant additional reasoning from investors.

When assessing the proposed liquidation preference, keep in mind it’s often based on three factors:

- The company’s risk profile (specific vertical/stages, deal competitiveness)

- The investor’s risk appetite (stage, fund, partner)

- The current economic/market conditions (hedging inflated valuations, general macro trends)

Founders can use these factors as starting points to discuss the rationale behind the investor’s proposed liquidation preference.

Anti-dilution provisions

Anti-dilution provisions offer another way for investors to protect their capital position—most commonly used in a down round, which occurs when the company they’ve invested in raises a sequential round of financing at a valuation less than the previous round.

After a down round, the existing investors’ shares are worth a lower price than previously. However, anti-dilution protection can prevent the dilution of ownership that would result from the lower valuation. There are two types of anti-dilution provisions: full ratchet and weighted average.

A full-ratchet provision means the portion the investor owns prior to the down round must remain unchanged after the round. To compensate for the lower share price, additional shares are allocated at no cost to the investor to maintain the same percentage of ownership.

Example of full ratchet provision:

An investor paid $10 per share for a 10 per cent stake in a company. In the next round of financing, the share price drops to $5, which dilutes the original investor’s ownership. With full ratchet anti-dilution protection, the existing investor’s shares are now valued at $5, and the company is required to double the investor’s shares to maintain its 10 per cent ownership. The issuance of new shares causes further dilution to the founder, as well as the new investors.

Because full ratchet protection heavily favours the investor and has the potential to cause significant dilution for founders, it is not typically included in a term sheet. A weighted average provision is a more common alternative.

With a weighted average provision, the existing investor also receives additional shares in the event of a down round. However, the number of shares given to the investor to offset dilution is calculated based on two factors: the lower share price and how many new shares are issued. This proportional approach results in a more incremental investment that’s less dilutive for the founders (and other shareholders) in comparison to a full ratchet provision.

What to consider when negotiating anti-dilution provisions

Full ratchet anti-dilution provisions are rare in term sheets because they can significantly dilute the founders’ equity and are not considered founder-friendly. They may also deter future investors who don’t have the same protections, or worse, set a precedent that leads to subsequent investors demanding the same (or better) anti-dilution terms.

Despite the potential for significant dilution to the founder, one could argue anti-dilution is less impactful than valuation or preferences for the simple fact that most investors typically don’t enforce them. It’s in their best interest to signal to other investors that the company is poised for growth and will, at times, waive their anti-dilution rights to bring more investors to the table.

Partnering with the right investor is often critical to a company’s success, and the term sheet can help set the foundation for a mutually beneficial relationship.

RBCx offers support to startups in all stages of growth, backing some of Canada’s most daring tech companies and idea generators. We turn our experience, networks, and capital into your competitive advantage to help you scale and make a meaningful impact on the world. Speak with a RBCx Advisor to learn more about how we can help your business grow.

Term sheet economics Q&A

What is a term sheet?

A term sheet outlines the overall deal and requests of an investor that is drawn up prior to finalizing an investment in a startup. Term sheets are also drawn up by banks for borrowers to outline the terms of a loan.

Is a term sheet legally binding?

A term sheet is not legally binding. It provides the foundation for the legal documentation that will follow once the agreement is finalized.

Is a term sheet negotiable?

Founders can negotiate the terms of a term sheet to ensure the deal is mutually beneficial to both the VC and the startup. In some cases, a founder may be presented with multiple term sheets which can provide leverage for negotiating the most ideal terms. However, too much negotiation may put the deal at risk, which is something every founder needs to consider when prioritizing which terms to focus on.

What is term sheet economics?

Term sheet economics generally refers to the terms that impact the return at the time of a company’s liquidity, including price, employee pool, valuation, anti-dilution, and liquidation provisions.