Part 1 of this series highlighted Canada’s maturing tech and venture capital ecosystem and its record year in 2021. With the exception of the United States, Canada now leads its peer group of developed OECD countries in venture capital investments per capita, ranking far ahead of countries like the United Kingdom, France, and Germany.

Yet Canada’s venture capital ecosystem remains disproportionately reliant on public sector financing. With an over-concentration of government capital, Canadian tech has a single exposed bottleneck, and this is a continued risk to scaling a resilient ecosystem.

Public sector participation in venture capital is appropriate and necessary because much of the value created by startups cannot be captured by individual shareholders but is rather externalized to the broader economy. Startups are nascent, wealth-creating – non-rent-seeking – enterprises, and therefore venture capital investments have the potential to create new jobs, technologies, and markets, while transforming communities in the process. However, while public capital can catalyze, it cannot scale an ecosystem.

Public investments into Canadian startups is a good thing, and I encourage policymakers to continue leaning into it. However, private capital markets must evolve to accommodate venture capital as an asset class, and private Canadian institutions and retail investors must participate if we’re going to sustain our success.

The Public Sector’s Outsized Role

In terms of capital investment, federal public funds flow down to Canadian startups through Crown Corporations – namely Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) and Export Development Canada (EDC), and through programs like the Venture Capital Action Plan (VCAP) and the Venture Capital Catalyst Initiative (VCCI).

The VCCI program allocates capital to Fund-of-Funds (FoF) investment managers and venture capital investors, who are in turn responsible for raising matching funds from the private sector and deploying that capital into individual tech companies. In the most recent instantiation of the program in 2017, the Government of Canada invested $371 million into the ecosystem, and in the 2021 budget the Government expects to allocate $450 million to the venture capital ecosystem with $50 million earmarked for life sciences.

By all accounts these programs have been a resounding success. Through VCCI and VCAP, the Canadian Federal Government has generated top-tier financial returns, stimulated tax income, spurred the creation of thousands of high-paying knowledge-based jobs, and fostered homegrown IP.

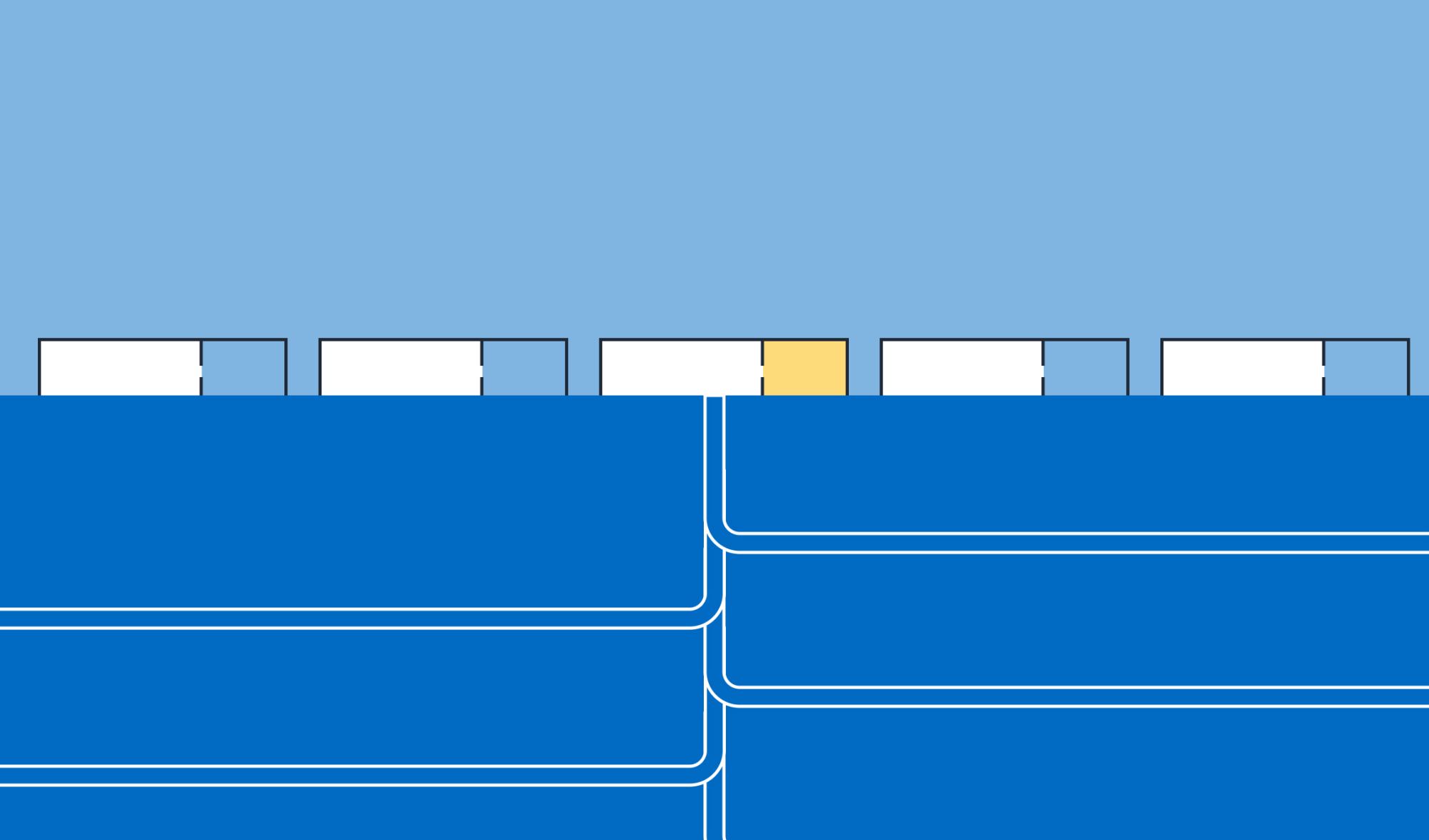

All this being said, herein lies the problem. We analyzed public data sources to approximate the scale and scope of public funding in Canadian tech. We estimate that a remarkable 35% of all dollars invested by Canadian venture capital firms into Canadian technology companies have a direct nexus back to government programs. 35% might seem stark, but in fact the government’s outsized influence is even more pronounced than that figure would lead you to believe. Hypothetically, if we were to extract public capital from the ecosystem, much of the residual 65% would also vanish from Canadian venture capital firms, and that impact would cascade down to tech companies. This is because investments in venture capital funds tend to coalesce around a handful of “anchor” or “lead” investors who commit a sizable portion of a fund’s capital and play a central role in standing-up and governing a fund. Remove the anchor, and much of the capital dissipates.

So, who are the most prolific anchor investors in the Canadian ecosystem? You guessed it, the VCCI FoF managers.

You can see the lifecycle of a government dollar in the chart below. If you sequentially track the regression of a Canadian dollar being invested in a Canadian tech company back to its source, often times you will find a public origin.

The conclusion is inescapable. The success of Canada’s tech and VC ecosystem has been induced by shrewd public policy and an injection of public capital. This is cause for both celebration and reticence, because while astute government action brought us here, what government giveth, government may taketh away.

Enhancing Public Sector Participation

With the preceding in mind, perhaps seemingly paradoxically, my principal recommendation is for the Federal Government to revise its notional 2021 VCCI allocation from $450 million to upwards of $1 billion – and this would still be rather conservative. Canadian FoF managers have demonstrated a repeatable ability to match public funds with private contributions, and to invest at scale into venture capital funds and startups – thus creating jobs and IP within our borders, and generating superior returns for taxpayers. Given the success of the government’s capital deployments thus far, and the growth of the tech ecosystem in parallel, there is a strong foundation on which to expand the new VCCI program.

Specifically, as it relates to the life sciences sector, the present estimated $50 million allocation is almost comically insufficient. Despite the pandemic reinforcing the importance of a vibrant life sciences ecosystem, and the absence of which having been revealed to be a national security threat, the government has not shown adequate foresight in supporting Canadian life sciences, despite the sector having made strides over the past few years with room to grow. In 2018, venture investments in Canadian life sciences languished at $650 million, while U.S. companies received over $30 billion, a ratio of more than 50x. By 2019, as relatively modest amounts of VCCI funds made their way to Canadian life sciences funds and companies, Canadian life sciences investments nearly doubled to over $1 billion, and have remained steady and growing ever since. The comparative gap between Canada and the U.S. had begun to close, until 2020 when Canadian investments grew at steady rate while U.S. investments catapulted to nearly $50 billion, likely in response to the pandemic.

I have no doubt that with the caliber of research and talent emerging from Canadian universities, coupled with a growing ecosystem of founders and funders, the Federal Government could comfortably invest multiples of its current modest allocation, and generate outsized returns on that investment.

Enhancing Private Market Participation

So far, I’ve argued that the concentration of public capital in Canadian tech constitutes a critical risk for the ecosystem’s long-term success, while simultaneously arguing for more public capital to be deployed towards venture capital. To reconcile these two positions, I believe that our undeveloped private retail markets need to be modernized and expanded to allow a free flow of Canadian private capital into Canadian venture capital.

Before proposing a remedy, let me explain why it’s so difficult for non-institutional investors to invest in venture capital and growth equity. In my view, the challenge can be summarized by a lack of access and natural diversification.

First with respect to access, venture capital and growth equity funds invest in non-listed equities, meaning the vast majority of private retail investors are prohibited from investing by the Accredited Investor rule. This piece of regulation forbids private individuals from investing in non-listed assets unless they meet restrictive pre-requisites.

In theory, this restriction is supposed to protect retail investors. In practice, it’s paternalistic and arbitrary. Regulators are sending a message to working Canadians that they’re not knowledgeable or sophisticated enough to invest in private assets, and that they can’t be trusted to manage their own risk.

Regulations aside, access for Accredited Investors and non-institutional investors is equally restricted by market dynamics. The venture capital space remains relationship driven. It’s a small, insular community, and the ability to invest in venture capital funds and high-growth startups will primarily depend on whether investors happen to know fund managers or startup CEOs. It’s arbitrary, local, and inefficient.

As it related to diversification, venture capital as an investment strategy is one of outliers. The majority of the economic value will accrue to a small subset of breakout companies, and by extension, the majority of the financial returns will accrue to the investors of those companies. Adequate diversification allows investors to increase their likelihood of exposure to generational companies and distributes the risk of inevitable write-downs.

In my view, venture capital funds are not in and of themselves vehicles of diversification. Venture funds tend to be thesis-driven investment vehicles, and they tend to focus their investment activities on a particular stage, sector, geography, and the list goes on. Investing in venture funds is akin to investing in individual stocks in public markets – you’re not betting on meta trends, markets, or industries, but on the performance of an individual, highly-volatile enterprise. Diversification in the world of venture requires exposure to multiple funds, spread across stages, sectors, geographies, and time horizons.

There’s no easy solution to what I’ve just described, but there are tangible blueprints for improving private participation in our venture markets.

First and foremost, we’re global laggards when it comes to private institutional investments in venture, and curing the discrepancy requires an attitude change. Our country’s capital markets commonly view venture capital as simply too risky an asset class. That’s an outmoded view internationally, but still omnipresent in Canada.

Beyond changes in outlook on the part of investors, there’s an evident lack of market makers in Canadian venture, whereas our U.S. peers have excelled. In addition to investing their own capital, U.S. financial institutions have built the rails to seamlessly move capital from both institutional and retail investors into venture capital funds. By co-investing alongside these major financial institutions, and benefiting from their scale and infrastructure, investors can attenuate both the access and diversification challenge.

Canadian tech is benefiting from sensational tailwinds. We’re well ahead of most of our peer group of OECD countries, with much room for growth. However, we need to be judicious in thinking about how we continue to scale the ecosystem and we will need private markets to dive in more deliberately and forcefully.

Enabling this transition will require financial institutions and asset managers to embrace venture capital as an important constituent of a complete investment portfolio, and we will need to develop formal channels to connect private capital to venture funds as our U.S. counterparts have done.

Finally, we will need to modernize our regulatory regime and better align with the United States – though granted this is unlikely to actualize. The balkanization of securities regulation in this country at the Provincial level creates encumbrances and barriers to scale that restrict entrepreneurial innovation in asset management. A more sensible approach would be to establish a single bi-lateral North American regulator to govern U.S. and Canadian capital markets under a single regime. This would spur Canadian innovation by creating a single point of compliance for access to the entirety of the North American market, while further enabling the free flow of capital across the border.

Next, stay tuned for Parts 3 and 4, where we’ll move beyond Canada and look at trends in venture more generally, and we’ll explore how the macroeconomy could transform the market in the coming months.