Exclusive trend analysis and insights into Canada’s venture capital ecosystem from John Rikhtegar, Director of Capital at RBCx

With so much attention paid to how much individual startups raise, analysis of a crucial part of Canada’s private capital food chain has been mostly neglected—until now. At LPFest, part of this year’s Startupfest in Montreal, John Rikhtegar, Director of Capital at RBCx, shared exclusive research and analysis of the last 10 years of Canadian venture capital (VC) fundraising activity.

While every month brings new headlines that celebrate successful funding rounds, the truth is none of this capital exists in isolation. The health of Canada’s startup ecosystem can’t be properly understood by simply analyzing how many startups get funded, or even how much they raise. Rather, we must study how venture funds, themselves, raise money from their own set of investors, otherwise known as limited partners or LPs.

Our in-depth study of VC fundraising activity since 2013 tells the story of a maturing ecosystem heavily influenced by macroeconomic factors. While the Canadian VC ecosystem in many ways mirrors that of the U.S., there are also key differences that present unique opportunities and challenges for investors and allocators, particularly at this point of the market cycle.

Here’s what our report reveals about the past decade of Canadian VC fundraising and the current state through the first half of 2024.

In cyclical markets, what goes up must come down

While venture capital isn’t new, it’s gained momentum and widespread attention as a standalone asset class over the last couple decades, and even more so since 2013. This coincided with a bull run that bolstered investor confidence and contributed to its allure as an attractive avenue to riches. Industry jargon like “unicorn” went mainstream, a proliferation of new emerging investors entered the asset class, VC fund sizes ballooned across all stages, and some successful VCs like Vinod Kohsla and Peter Thiel even became celebrity-like figures. Valuations soared, particularly in the U.S. during 2020 and 2021, and fortunes were made. This all led to an air of exuberance and, for some, invincibility.

In 2013, the launch of the federally-funded Venture Capital Action Plan (VCAP) kickstarted a new and exciting era for our Canadian venture capital ecosystem. From 2013 to 2016, the $400-million program backed four private-sector led funds, which led to over $900 million CAD in private investor capital entering the startup ecosystem and investments in over 100 Canadian startups. The federal government committed $1 for every $2 committed by the private sector, up to $100 million per fund.

In 2017, the federal government boosted this support with the Venture Capital Catalyst Initiative (VCCI), which raised $1.76 billion for Canadian VC funds, $1.4 billion of which came from private investors.

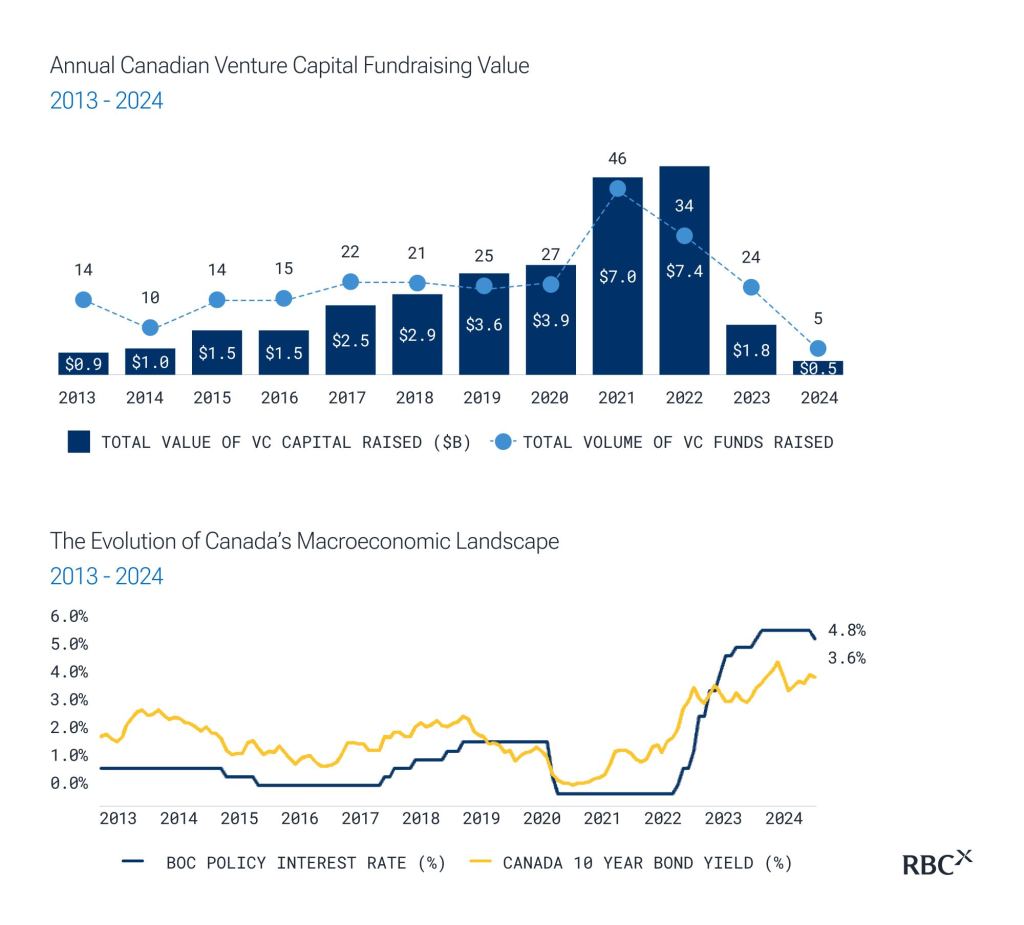

From a macroeconomic perspective, following the Great Recession, monetary policy loosened. Zero-interest rate policy (ZIRP) aimed to restore national economies by incentivizing investment in not just all assets, but riskier assets. The idea was that this would spur growth and generate wealth, which would then trickle down throughout the economy. In 2013, Canadian VC funds raised $0.9 billion. In 2015, they raised $1.5 billion and, in 2020, they raised $3.9 billion.

Sources: Pitchbook, RBCx proprietary data, and publicly available information.

Macro factors were already spurring a decade-long bull run when the pandemic hit. In April 2020, the Bank of Canada (BoC) also began quantitative easing (QE) with the purchase of $1 billion in government bonds—they would continue QE until late 2021 ultimately purchasing $340 billion in government bonds.

By buying up government bonds, an extremely safe asset class, the BoC further encouraged borrowing and investment in riskier asset classes, like VC-backed startups. LPs flocked to invest in VC funds of all types and stages. In 2021, Canadian VC funds raised a staggering $7 billion and, in 2022, they raised $7.4 billion as a result of fundraisings that kicked off during the peak of 2021, but closed a year later.

Money was cheap, so it made sense to invest it as widely as possible. There appeared to be potential returns everywhere, and sitting on cash reserves or investing in safer asset classes made little sense as ZIRP and QE made returns negligible.

A similar trend occurred in stock markets, where more and more investors ignored market fundamentals and bid up equities beyond their real worth. However, while many investors are familiar with the boom-and-bust cycle of stock markets, the relatively newer Canadian VC landscape’s trajectory remained a bigger question mark.

As it turned out, VC funds are subject to the same cyclical pattern as stock markets, with stages of expansion, peak, recession, and recovery. When the BoC ended QE and raised interest rates in response to rampant inflation, VC funding effectively dropped off a cliff in 2022 as borrowing became expensive to discourage frothy spending. As a result, safer asset classes once again became more attractive. In 2023, compared to the year prior, the amount of capital raised by Canadian VCs dropped by an astonishing 76 per cent. Halfway through this year, Canada’s VCs are on track to raise the least amount of money in a decade.

While VC fundraising and deployment both follow a cyclical pattern, not all stages are evenly distributed over time. Rather, the expansion period is gradual, while the peak and recession periods are sharp and abrupt. Money quickly flees when macro conditions change. As the BoC begins to slowly loosen monetary policy once more and lower interest rates, this cycle will begin again.

Established firms are reaping the rewards

Notably, not all VC funds experienced the capital flight of 2023 equally. LPs looking to safeguard their investments and mitigate risk began to prioritize quality over quantity. This meant an emphasis on experience and proven results over unpredictability and experimentation.

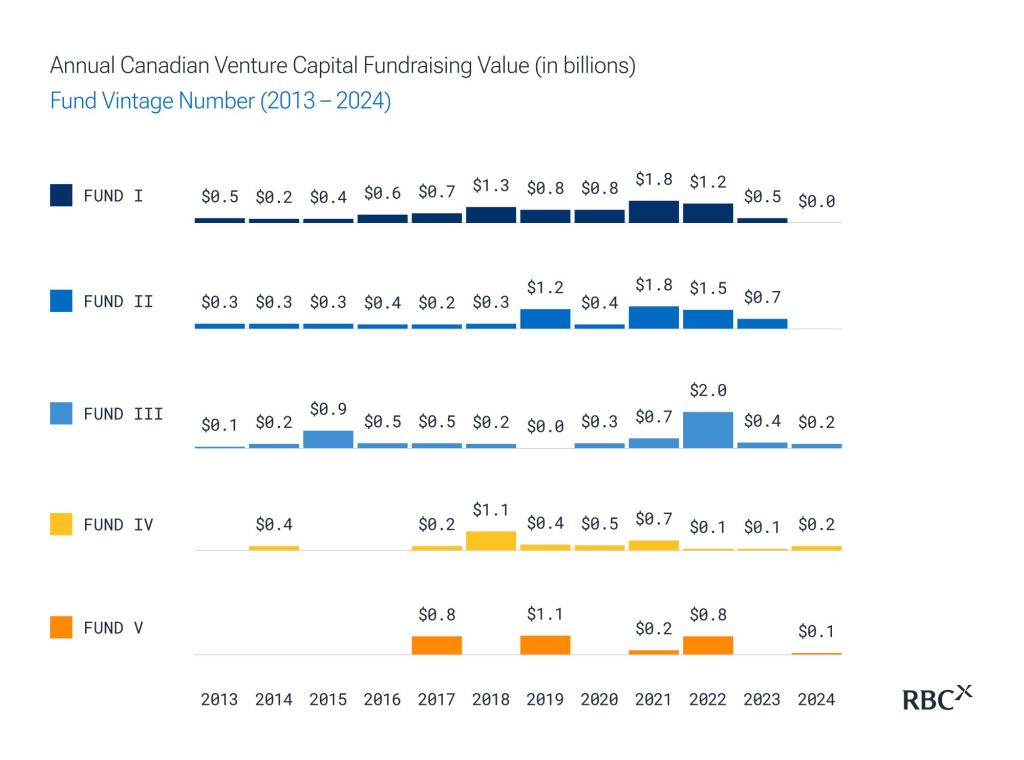

While the peak years of 2021 and 2022 were two record years for VC funds across all stages, emerging VC firms experienced the sharpest capital flight as macro conditions changed. Emerging funds (I-II) hit a fundraising peak in 2021, yet this year is on track to have the lowest volume of Fund I and Fund II raises over the last decade. This is because younger VC funds, by their very nature, don’t have the same proven track records or ability to showcase successful exits as later-stage VC funds and are therefore perceived to be riskier.

To illustrate the stark difference between different phases of the VC funding cycle, in 2013, 56 per cent of all VC capital raised in Canada went to Fund Is. In 2024, only one per cent of all VC capital raised in Canada went to Fund Is as LPs shifted to more established names and capital concentrates in proven investors. This is the first year in which established funds (IV+) surpassed emerging funds in both value and volume.

Sources: Pitchbook, RBCx proprietary data, and publicly available information.

This represents a change in investors’ risk tolerance, but it also represents a maturation of Canada’s startup ecosystem as more VC funds have successfully raised subsequent funds than a decade ago. This is a sign of health and steady growth.

Venture funds have their own graduation rate dynamics

The vast majority of Canadian VCs raise a new round every three to four years. This means many funds that had closed in the peak years of 2021 and 2022 are either currently or about to embark on raising their next fund. More challenging conditions raise the risk that these funds don’t graduate to the next stage. The decreasing graduation rates across subsequent funds is a function of:

- Investors not meeting the partnership or return expectations initially set out with their LPs which has impacted their ability to raise subsequent funds, and

- Many of Canada’s funds being from emerging firms and, as a result, have not been in business long enough to test the market and raise subsequent funds.

Over the last decade, only 50 per cent of Canadian Fund Is raised a Fund II, and only 50 per cent of Fund IIs raised a Fund III. However, the largest dropoff occurs between Funds IV to V, with 61 per cent of funds not graduating.

Equally important to note, emerging VC funds have only held a 16.2 per cent probability of becoming an established name (+IV).

“Just as startups have their own graduation rates, with only so many seed-stage companies making it to series A, and so-on, it is natural to have the same graduation rate dynamics exist at the investor level as well, given these are the firms investing in the companies themselves,” says Rikhtegar. “As both founders and investors progress on building their companies, whether that be a company with a product or a portfolio of investments, eventually dispersion will show and the very best will pull away from the pack.”

Notes: (1) Excludes all opportunity, continuity, and alignment funds. (2) Eligible firms included have raised at least one fund between 2013 – 2023. For eligible firms with funds raised prior to 2013, this analysis incorporates those prior funds to ensure accurate graduation rates. (3) Graduation Rate only considers funds that have raised prior to 2022; given funds raised afterwards would not be expected to have raised a subsequent fund. Sources: Pitchbook, RBCx proprietary data, and publicly available information.

Typically, Fund III is where push really comes to shove and VCs must show real returns to their investors. Pitches and projections must turn into cash as startup investments made nearly a decade ago in Fund I are expected to have grown rapidly and reached an exit.

However, macroeconomic conditions haven’t just impacted VC funds, they’ve also impacted the startups they invest in. Exits are harder to come by and less lucrative than they were just a few years ago. Private sector acquirers are more wary, less competitive, and are more realistic with present-day valuations, while going public isn’t as enticing when market capitalizations and trading volumes are also much lower than in peak years.

If Fund II and Fund III general partners (GPs) have to raise subsequent funds without a record of returning material cash to their investors, they could find themselves in difficult positions and the drop-off between emerging and established VCs could worsen.

This threatens to disrupt the steady and gradual maturation of Canada’s VC ecosystem at a critical time.

“First, just because we are seeing less capital being allocated to the venture capital asset class over 2023 and 2024, does not mean that long-term returns will be lower,” says Rikhtegar. “In fact, with less relative capital being allocated, the past two and next two years represent one of the most opportunistic periods to invest in venture capital that we have seen in over a decade as capital will be concentrated in the very best investors and founders, which will produce some of the best vintage returns for Canada.”

Unique opportunities for Canadian VCs

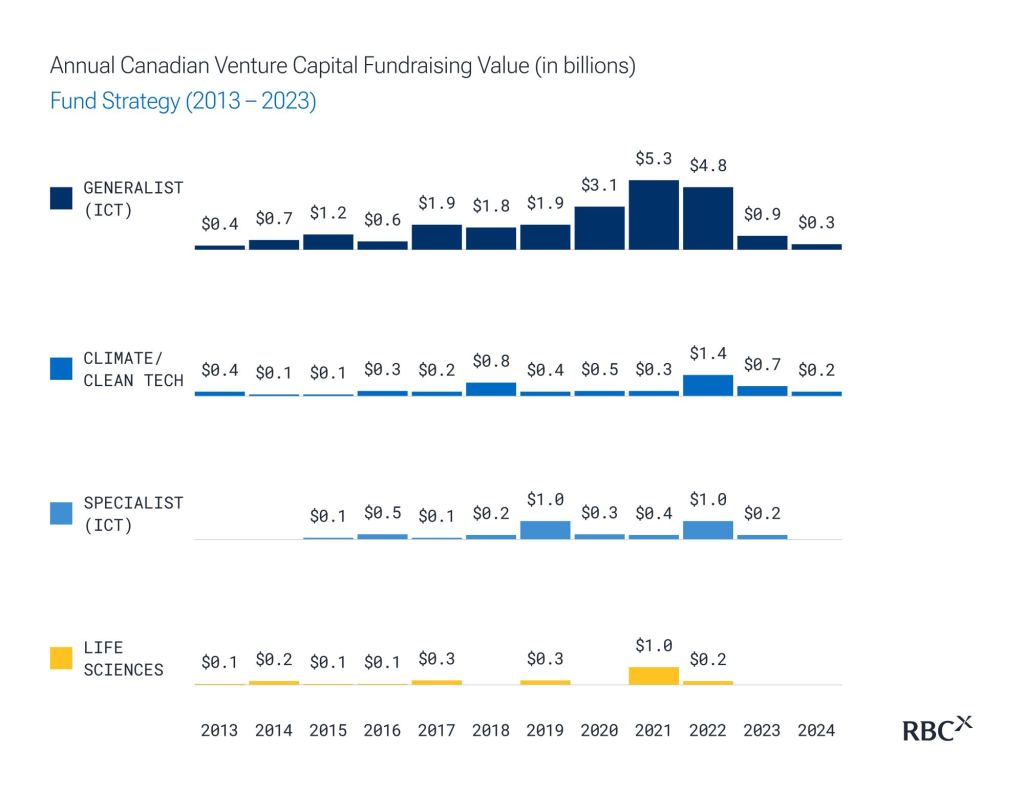

While there are certainly continued challenges ahead for Canadian VCs, there are also unique opportunities. Over the last 10 years, 67 per cent of all Canadian VC capital raised has been from generalist (ICT) funds that invest in a wide variety of startups rather than focusing on a specific sector.

Sources: Pitchbook, RBCx proprietary data, and publicly available information.

This is in large part due to the relative youth of Canada’s startup ecosystem, which lacks the depth to support a large number of specialized funds. However, there is one sector that’s beginning to stand out as an opportunity for specialization.

Though only 7 per cent of Canadian capital raised over the last decade has been in life sciences, Canada punches above its weight in the sector and has produced several significant exits, including Chinook Therapeutics (acquired for $3.2 billion USD in 2023), Inversago Pharma (acquired for $1.07 billion USD in 2023), and Fusion Pharmaceuticals (acquired for over $2 billion USD in 2024).

Life sciences startups aren’t always as attractive to investors as startups in other sectors because they often require longer timelines to realize returns. However, this area appears to be entering a golden era of innovation with potential for massive profits.

Additionally, many life sciences startups prefer to work with specialized funds because of their in-depth understanding of the sector and ability to provide expert guidance and connections.

The small number of specialized life sciences funds compared to generalist funds means there’s less money chasing what’s trending towards big opportunities. Less competition presents GPs with a chance to get in early before the space becomes more saturated.

More exclusive insights to come

Stay tuned for more analysis of Canada’s maturing VC ecosystem and insights that industry leaders can draw on as we enter the building stages of a new fundraising cycle.

RBCx offers support to startups in all stages of growth, backing some of Canada’s most daring tech companies and idea generators. We turn our experience, networks, and capital into your competitive advantage to help you scale and make a meaningful impact on the world. Speak with an RBCx Advisor to learn more about how we can help your business grow.